We are officially in the dog days of the summer. It is the portion of the long Wiffle® Ball season where teams are grinding it out under less-than-ideal conditions with their eyes set on October. That’s certainly the case for the 4th Mid Atlantic Wiffle® Ball tournament of 2017.

Five for Friday: The Sub-1.00 ERA Club

Through three tournaments, there are five pitchers in Mid Atlantic who have thrown at least 19 innings and have an ERA under 1.00 – Jarod Bull, Ryan Doeppel, Danny Lanigan, Nick Schaefer, and Connor Young. While they all share the same minuscule earned run average, none of the five pitchers went about it in quite the same way.

2017 Tournament #3 Recap - "A Whole New Ball Game" (July 15, 2017)

2017 Tournament #2 Preview - "It's Like Deja Vu All Over Again!"

A Pitching Performance for the Ages: Fact or Fiction?

Chris Bechtold scarcely knew of competitive Wiffle® Ball when he and his old brother, Greg, decided to enter the 1995 North American Wiffle® Ball Championships in Cincinnati, Ohio. By the end of the tournament, Bechtold etched his name in Wiffle® Ball tournament lore with a pitching performance for the ages.

But did it really happen?

The March 10, 1996 edition of the Chicago Tribune contained an article about the Illinois resident. According to the article, Bechtold – who played as one half of a two-man squad with his brother Greg – threw four one-hitters and six no-hitters during the course of the three-day tournament. If that wasn’t impressive enough it gets better! The topper is that – according to the Tribune – Chris Bechtold struck out 214 of the 222 batters he faced over the course tournament!

It is difficult to even process those numbers.

The strikeout total itself is simply staggering. According to the Tribune, Bechtold struck out 96.3% of the batters he faced over the course of that weekend tournament. But it is not just the strikeout numbers that are mind blowing. Based on that one bit of information, we also know that only eight plate appearances against Chris ended in something other than a strikeout. That means at the most he allowed eight base runners (walk or a hit) – that’s a mere 3.7% of the total batters he faced! If Bechtold recorded any outs with something other than strikeout, that already impressive figure drops even further! Those are not just video game numbers, they are borderline unbelievable.

The reported feat is so great – so above a normal tournament performance – that it is a little hard for me to believe it is true. Don’t get me wrong, I hope it is true and if there were no reasons to question the claim, I wouldn’t. The statistics, however, beg as many questions as they answer.

Thankfully, the Chicago Tribune provides a few more numbers on Chris Bechtold’s legendary performance. Let’s start with that first, eye-popping paragraph paraphrased above that addresses Bechtold’s statistical achievements at the 1995 North American Championship.

Bechtold was named most valuable player of the North American Wiffle Ball Championships after pitching six no-hitters and four one-hitters in 12 tournament games while striking out a dizzying 214 of 222 batters he faced.

This sentence raises many questions.

The first question is just what was Bechtold’s workload during the tournament? Six no-hitters and four one-hitters amounts to ten total games. The only North American Championship rule book I currently have at my disposal is the 1997 version which lists the number of innings per game as seven. If Becthold faced every single possible batter in ten, seven inning games he would have had to record 210 outs. The Tribune has him striking out 214 batters – four more than he would have faced during regulation. There are two explanations for this discrepancy – either something is afoot or the Bombers played into extra-innings at least once.

The author writes that the Bombers played “12 tournament games”. It is possible that Chris’ brother Greg pitched the other two games for his team. If so, nothing really changes in terms of the plausibility of the feat. However, if Chris pitched all twelve games and two weren’t no or one hitters, the result is that Chris pitched two games where he let up two or more hits. If so, we have now accounted for all 222 of the batters he faced (214 K’s and eight hits). If true, Bechtold did not walk a single batter during the tournament.

Fortunately, there are more numbers cited in the article. Some potentially clear up what happened while others shed further doubt on the veracity of the remarkable accomplishment. Below (in order of appearance in the article) is every other relevant number cited.

“Chris, a lefthander, allowed only eight batted balls in 12 games while recording his 214 strikeouts.”

“The Bechtolds advanced to the title game but lost 2-1 to a team from New Jersey in extra innings.”

“In wiffle ball, only four players are allowed in the game at any one time, and games are six innings.”

Now we are getting a clearer picture! With two references to twelve games – including one that specifically states Chris pitched all twelve – it is reasonable to assume that Chris pitched in twelve tournament games. The article also states that games were six innings and we will go with that, while assuming that the game length increased sometime after the 1995 tournament and before the 1997 tournament. Taken together, that means Chris would have had to record 216 outs.*

* There is a caveat of course – losses. Bechtold’s arm might have been spared a half-inning or two if the Bombers lost one or more games before the extra-inning finals. Delving into those scenarios without additional information is going to make my head spin even more so than it already is so for my sake, we will assume that Chris pitched six innings+ in all twelve games.

Let’s see if the numbers still hold up. Chris had to record 216 outs to get through twelve six inning regulation games. He struck out 214 batters which meant one or two batters made an out on a ball in play (it could be only one if that one ball in play out was a double play). Assuming two balls in play were recorded for an out, that’s all 216 outs accounted for. Then we have the eight hits (four one-hitters and presumably two two-hitters), which gives us a problem. That is 224 total batters and the article lists only 222. The solution to that might be the aforementioned double plays. A batter that records a hit can still record an out (via a double play) so they are not mutually exclusive. To get back to the magic 222 batters faced number we can make the leap that Greg was able to maintain his concentration during his brother’s strikeout parade in order to wipe out two of the eight base runners via double play.

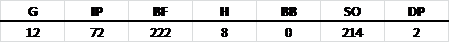

If Chris did indeed pitch every regulation inning (six) or twelve tournament games while allowing eight hits as the article implies he did, then his 1995 championship stat line might have looked like this:

The numbers all work out, even if the line is getting more and more difficult to believe. Plus, there is one final winkle. As stated above, the article gives specific details about the final game of the tournament including that the Bombers lost 2-1 and that the game went into extra innings.

The score doesn’t necessarily present an issue. We already know (or rather assume based on the Tribune article) that Chris allowed 8 hits and that there were a pair of games where he allowed two hits. It is possible that the championship was scoreless entering the 7th inning, the Bectholds scored in the top half of the inning, and then the winning team (Team Trenton) hit a single and homerun to walk it off. It is also possible that Trenton hit two solo shots (one in regulation and one in extras) to win the title. That doesn’t present any problems.

On the surface, the final game going to extras does present a potential issue because with twelve six-inning games and eight hits, we have already accounted for all 222 batters faced. The simple answer is that Bechtold never recorded an out in the seventh inning of the championship game. If he allowed the game winning hit(s) with no outs, the math still holds together.

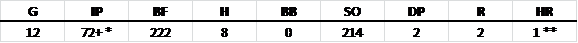

With that final piece of the puzzle, Chris Bechtold’s line – based on the information provided by the Chicago Tribune – would have to be this:

* Did not retire a batter in the 73rd inning.

** Could be 2 HR’s

That is some impressive line. But is it real?

My gut says “no”. I have seen some impressive Wiffle® pitching performances in my life and have heard about even more, but none that even approaches this level. At times, Wiffle® ball has been dominated by pitchers and from what I understand that was the case at the highest competition levels back in 1995. Chris was a quality baseball player (the Tribune states that he tried out for the White Sox the prior summer) and Greg says Chris reached speeds of 90 MPH with a Wiffle® ball. It is certainly possible that a pitcher with that profile during an era without a lot of great hitters could go on a strikeout rampage.

The fact that the provided information leaves no room for even a single walk is what I cannot get passed. To have that sort of control with a Wiffle® ball (or a baseball!) while facing a relatively large number of batters is unthinkable to me. Sure, maybe guys were swinging out of their shoes and helping him out on balls out of the zone. I don’t know about you, but if I were facing a guy like Chris Bechtold was described to be I am going up to the plate at least once with the bat squared firmly on my shoulders and praying for a walk. I am guessing I would not be alone in the utilizing that strategy. It stretches the realm of disbelief that Chris Bechtold could face that many batters, having nasty strikeout stuff, and somehow did not walk a single batter of the 222 he faced.

None of this is meant as a character attack on Chris or as a question of the Tribune’s reporting. The quotes from Chris in the article paint the picture of a guy that is very amused at the odd way he earned his fifteen minutes of fame. He doesn’t come off in the piece as someone who way takes his Wiffle® accomplishments more seriously than they should be taken. Perhaps he understood the frivolity of the entire situation and in lieu of actual score books, backed into a stat line that conceivably could have happened. The fact that the hit and strikeout numbers perfectly add up to the total number of batters faced makes me believe that at the very least someone – Chris or the author – gave thoughtful consideration to making sure the entire thing tied together.

Regardless of whether Chris Bechtold had the greatest tournament pitching performance in competitive fast pitch Wiffle® Ball history or whether the account given by the Chicago Tribune is an exaggerated re-telling of a merely excellent performance, I love Wiffle® stories like this one. A lot of our first experiences with the ball involve pretending to win Game 7 of the World Series by hitting a lobbed ball over the fence into the neighbor’s yard. Many of us play Wiffle® ball now as adults because of the way the game and ball allow for high school or college baseball flameouts to be superstars (or in my case, an occasional contributor) in their own right. Wiffle® Ball is game that allows for impossible dreams to (sort of, kind of) become reality. What is Wiffle® Ball without stories of regular everyday Joes (Chris Bechtold works for his family’s insurance company in Illinois) turning in Herculean athletic feats, exaggerated or otherwise?

Note: There are ways to possibly verify the claims made in the Tribune article and perhaps check if the assumptions that I made are indeed accurate. For prosperity’s sake – and because I’ve already come this far – I plan on following up with players at the 1995 North American Championship like Mike Palinczar of Team Trenton and Jerome “The Legend” Coyle of the Lakeside Kings to test their memory and see what they can recall of Bechtold’s 1995 tournament performance. There is also Chris Bechtold himself who I would love to speak with and see what he remembers. Stay tuned.